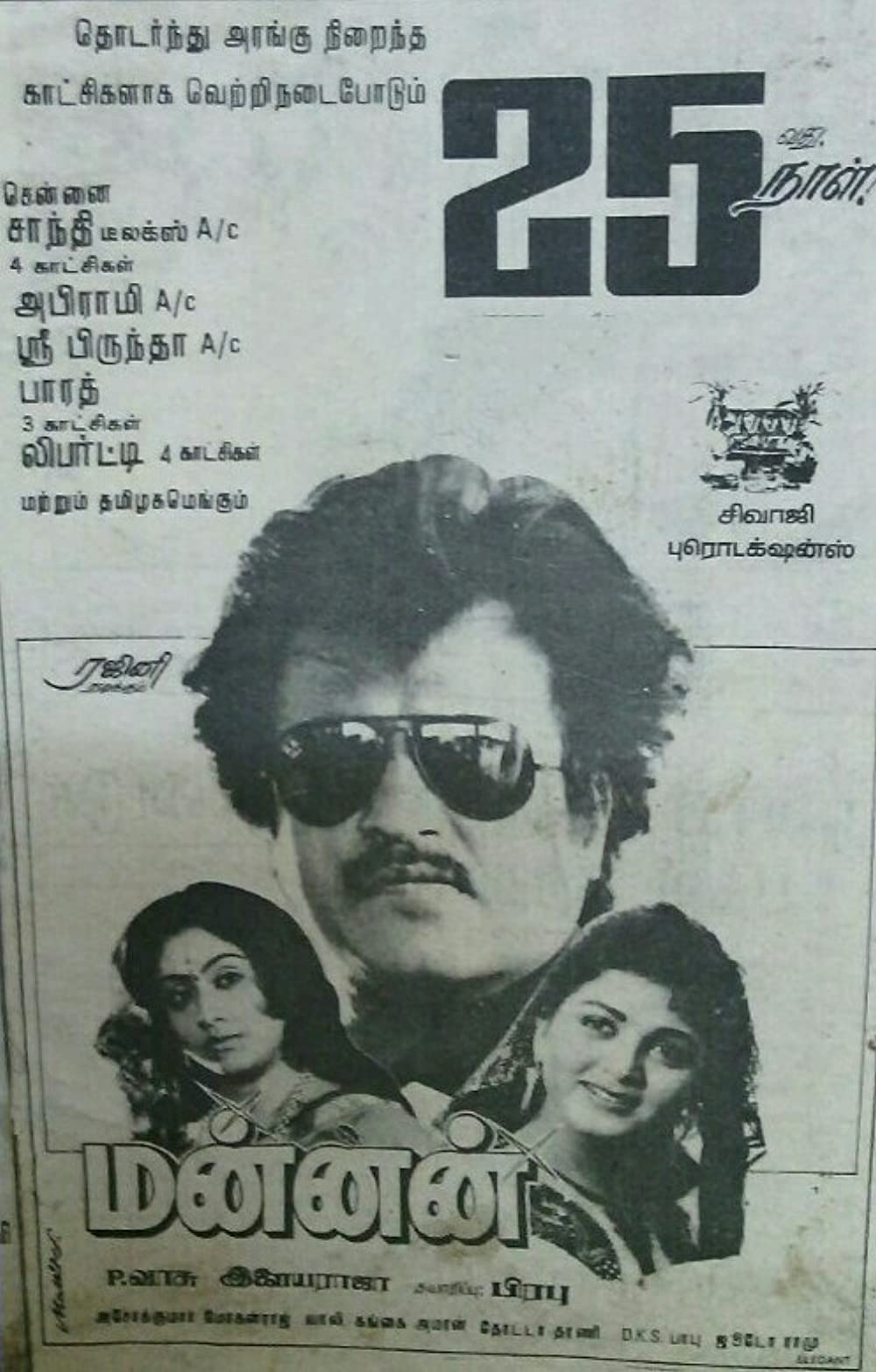

Rajinikanth after swaying between the villain and the angry young hero in the 70s and 80s was already a Superstar by the time Mannan had released. This P. Vasu’s directorial was only the start of Rajini’s silver jubilee films for the 1990s.

Vijayashanti, the female lead, who predominantly worked in Telugu industry had already garnered the titles of “Lady Superstar” / “Lady Amitabh” by featuring in multiple women-centric films and as an equal to the Telugu actors Chiranjeevi and Balakrishna in dozens of their films. She was also the only female actor demanding the highest remuneration in India, equal to her male co-stars.

Revisiting the plot:

Mannan is a story of how Shanthi Devi (Vijayashanti), an assertive, aggressive CEO & number one young industrialist of India is tamed by Krishna (Rajinikanth), a mechanic who works in her company—because women can be anything but angry.

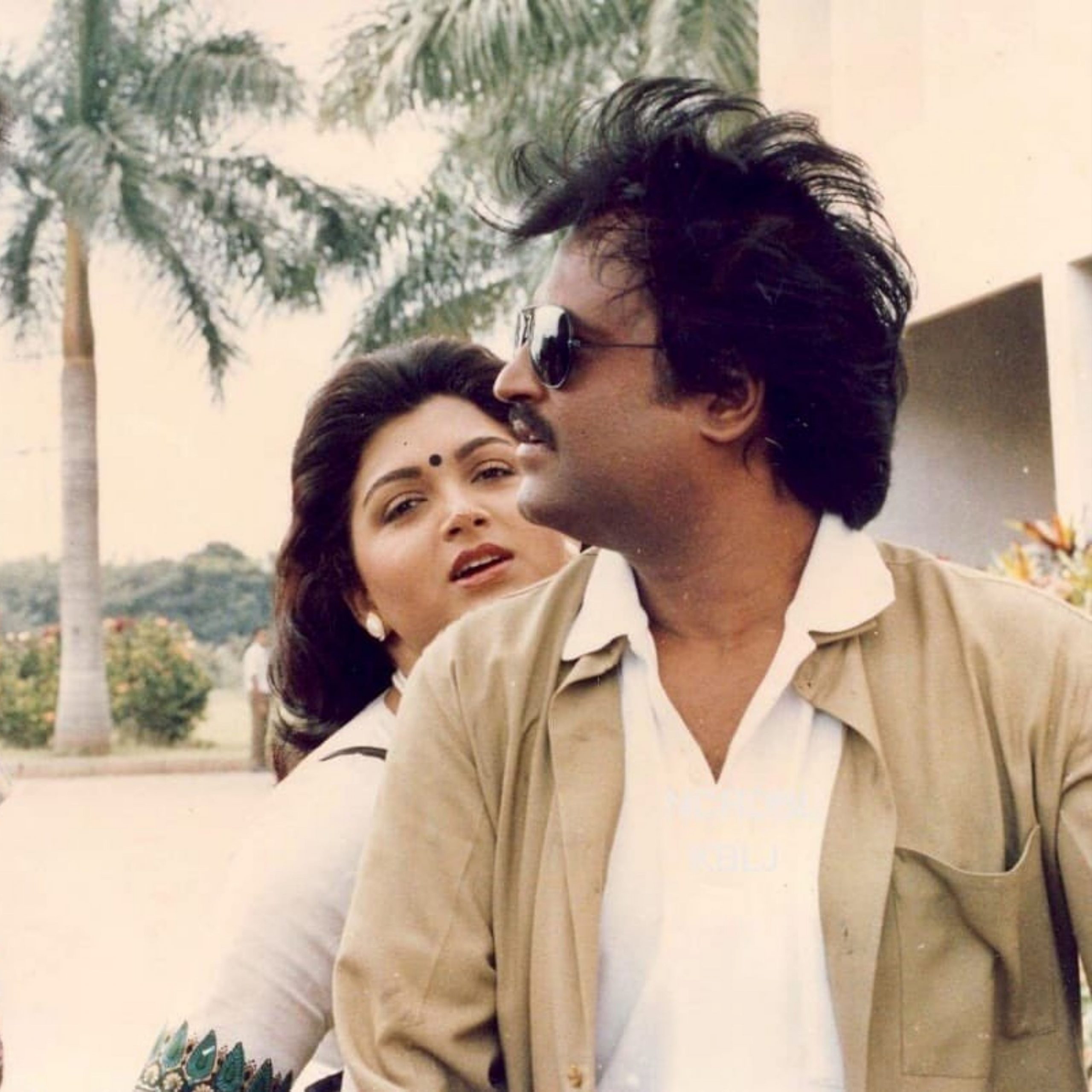

Shanti and Krishna since their first scene are ironically not very different from each other as most audiences were conditioned to perceive. They are both dominant personalities who have great love and respect for their family. They are strong-willed, self-righteous, intolerant to injustice, and prone to violent outbursts and try to take control of the other when they don’t fall under their ordinance. The only difference between both is their gender and class.

Misguided Feminism:

Popular films have often falsely portrayed feminism as a man-hating phenomenon and feminists as a threat; Mannan is no exception. During a television interview that features her as the No.1 industrialist in India, Shanthi says, “I never liked to be in the 2nd position” to which the female interviewer quickly responds, “After you are married, won’t your husband be No.1, won’t you obviously be No. 2?” Shanthi replies that her husband will be No. 2, and it’s best if men took care of the home, while women ruled the world. This is not well received even by her father who otherwise is supportive of her daughter. He says, “No self-respecting man would marry you if he watches this interview.”

Naturally, her man-hating demeanor overpowers her assertive and independent actions for the audience. In addition to Shanti, there are two other main female characters in the film, who in Krishna’s and everyone’s eyes are the epitome of femininity and culture: Krishna’s mother and Krishna’s love interest Meena (Kushboo). The media often showcase culturally normative forms of masculinity and femininity. In virtue of that, Krishna’s mother who is unable to walk is seen synonymous with the goddess and Meena who sacrifices her love for Krishna and assumes widowhood, much like Sumathi (Suhasini Maniratnam) from Dharmathin Thalaivan (1988), another Rajini film, are seen diametrically opposite and non-threatening to the culture. Meena, Shanthi Devi’s secretary, expresses her love to Krishna when she learns that her masculine hero is reduced to the role of a caretaker. She moves in with Krishna’s ailing mother to be her caretaker, reducing herself to a nurturing role is the ‘good’ woman. While Shanthi Devi who is rich, assertive, sometimes even arrogant and loudmouth is portrayed as the ‘bad’ woman.

The Politics Of Women’s Anger:

When a female character is angry on screen, it is undeniable that by the end of the film the hero will/should tame her and put her in her place. An angry woman is never a person that a hero can take home to his parents. The semiotics of that character mostly revolve around her short hair, ‘modern’ clothes and foul language which, clearly, in patriarchal society is a definition of a bad woman. In the case of Mannan, Shanti Devi’s first full scene is when she slaps her employee for an error. Workplace violence (one slap is also violence) is wrong no matter the gender, but Tamil cinema has successfully established that when a male actor slaps it is heroic—credits to the innumerable introductory fight scenes of heroes. In an almost intermission scene Krishna storms into Shanthi’s office and slaps her 5 times, a response to her slapping him in the previous scene. He adds that she’s forgotten Tamil culture and advises to keep his violence against her behind the doors else the shame will fall on her.

Since Shanthi & Krishna’s first collision, Krishna never misses a chance to emphasize how a woman’s anger would set up as the root cause of her downfall. He constantly reminds her, the CEO of a company, that she is not ‘woman enough’ to receive his respect. Respecting women who abide by your notion of femininity & culture, respecting women you are related to is not ‘respecting women’. Women deserve respect because they are humans. Krishna, unaware of this, is never hesitant to preach how an ideal woman should be. He says, “Women should bow their heads down and walk with humility.” Words like adakkam & amaithi (transl. patience) is repeated countless times to shame Shanthi: “However courageous one might be, only a patient woman can lead an honorable life.” “Patience is more important to a woman than beauty, patience is more important than intelligence,” he says.

In the end, Shanthi who is on the verge of self-destruction, kneels at his feet. Shanti is defeated and reconstituted within the mold of the good woman. Her masculine ambition and assertiveness are replaced by shyness and submissiveness. She accepts her role as wife and submits to the rule of her husband. Far from the angry young woman she was at the beginning of the film, she is now shown as happy and put in her place—the kitchen and the bedroom. While Meena the unthreatening, self-sacrificing woman is made the CEO of the company.

An angry woman equals a ‘bad’ woman who is often the undesirable love interest who puts off the hero like in the case of Anitha (Reema Sen) in Selvaraghavan’s Aayirathil Oruvan (2010), Nilambari (Ramya Krishnan) in Padayappa (1999). Even in Kamal Haasan starrer Panchathanthiram (2002), which is a comedy film, when Mythili (Simran) gets angry over her allegedly cheating husband, her anger is portrayed as something irrelevant and not called for.

In an industry where most sought-after male actors have earned their place by essaying the roles of youth angry rebels, Tamil slang terms like bajari and sorna akka are derogatory terms for angry women while rowdy, pokiri, porukki are glorified terms for men, let alone be movie titles—it not unclear why arrogant/angry women characters are shown as someone who needs to be tamed and shown her place. Women’s anger and desire to win are treated as pathological and tragic, hurtful to everyone around her. Comparatively, for men anger is portrayed as righteous, and their desire to defeat is a natural extension of their masculinity.

In a patriarchal country like India where gender roles are socially constructed, the media retains a powerful role in this process with its huge popularity. The case of Mannan (1992) defining norms of femininity & masculinity is one of many and not much has changed in these three decades. In Sigappu Rojakkal (1988) Kamal Haasan made it stylish to kill a certain kind of promiscuous and liberated woman. In Sivakasi (2005), we have Vijay moral policing a policewoman who ought to treat the male accused with more respect because after all, she is a woman and she can’t forget this just because she is wearing the khaki uniform. STR killed any woman who holds a drink or dresses provocatively in Manmadhan (2004) and Dhanush sang abusive lyrics about women. Let’s not forget Sivakarthikeyan’s Mr. Local (2019) is heavily inspired by Mannan (1992) itself.

Films do not just reflect society—they contribute to society. Constant portrayal of female characters as second-class citizens in films contribute to women’s subordinate status in society. Girls who grow up in a media-rich environment, are bound to see images that reinforce culturally normative forms of femininity. Before girls reach adolescence, the time when most begin to develop individual identities and prepare for future roles, they are likely to have seen countless media images of women that emphasize feminine qualities and urge conformity to traditional stereotypes. Hence, it becomes extremely crucial to continue revisiting older films with a fresh pair of gender lenses.

References:

Karupiah, P. (2016). Hegemonic femininity in Tamil movies: Exploring the voices of youths in Chennai, India. Continuum, 30(1), 114-125.

Krishnakumar, Ranjani (2017, April 24) Tamil Film ‘mannan’ Presses The Limits Of Using Violence On A Female Nemesis. Pop Matters

Nakassis, C. V. (2017). Rajini’s Finger, Indexicality, and the Metapragmatics of Presence. Signs and Society, 5(2), 201-242.

Sathiyaseelan, S. (2019). Women vs modernity in Rajinikanth’s Tamil-language films: The mother, the good woman, the modern virgin and the angry feminist. Studies in South Asian Film & Media, 10(2), 163-178.